Random lasing

Nanoscale devices require the use of nanolasers with ultra-small size and almost zero threshold [Science 314, 260 (2006)], the required energy to achieve laser oscillation. However, reducing the size of the lasing volume implies two main challenges: the design of an optical feedback mechanism operating at the nanoscale and a very efficient excitation given the very small amount of gain material. Nanostructuring the gain material simultaneously solves these two issues: it creates a feedback mechanism due to interference with the nanostructure while, at the same time, enhances the light-matter interaction improving the gain efficiency and minimizing its threshold. Serious efforts have been made to achieve nanolasing by engineering very precise nanostructures where, again, structural imperfections impose severe performance limits. However, multiple scattering of light offers an alternative solution to this challenge. Multiple scattering retains light within the gain region compared to the bulk unstructured material maximizing the optical gain and eventually leading to lasing [Nat. Phys. 4, 359 (2008)]. The necessary condition for this so-called random lasing is that the optical gain overcomes the leakage out of the structure. So far, random lasing has been mainly observed operating under weak multiple scattering which limits its applicability as it leads to multidirectional lasing emission and a poor lasing mode confinement which gives rise to strong mode competition [Phys. Rev. A 76, 033807 (2007)] and chaotic laser emission [ ]. The random structures used to obtain random lasing are mainly composed by scatterers with very different shapes and sizes like powdered laser crystals [Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 2278 (1999)]. In these structures, the lasing emission wavelength is totally determined by the maximum of the gain spectrum.

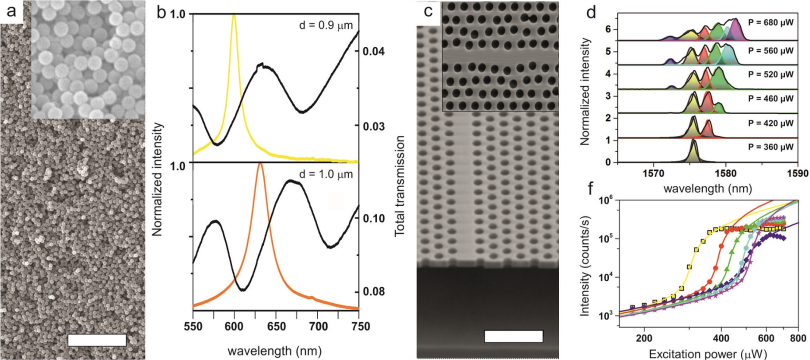

Fig. 1. Random lasing in disordered nanostructures

(a) Scanning electron image of a photonic glass made of polystyrene microspheres. The scale bar is 20 microns. (b) The diameter of the spheres determines the random lasing emission wavelength of a photonic glass containing an organic dye. (c) Scanning electron image of a photonic-crystal waveguide obtained by omitting a row of holes in a photonic crystal. The scale bar is 1 micron. Anderson-localized modes in this structure provides the necessary optical feedback for random lasing when a quantum well is embedded in the structure. In that case, multimode lasing is observed (d), showing a very stable output emission (f). Figures taken from Ref. [Nature Photonics, 2, 429 (2008)] and [Nature Nanotechnology, 9, 285 (2014)].

During my research career, I have explored different methods to introduce a wavelength tunability mechanism in random lasers and to improve their output stability by engineering the scattering properties of the complex network. For example, during my PhD we achieved a method to introduce a wavelength tunability mechanism in random lasers by using photonic glasses (see Fig. 1a). The equal shape and size of the spheres leads to resonant multiple scattering of light as shown in Fig. 2a and, when sufficient optical gain is embedded in the structure in the form of, e.g., an organic dye, the lasing wavelength emission is determined just by the sphere diameter as shown in Fig. 6b. Such a system is a dispersive random device with an a priori designed lasing peak within the gain curve. In a photonic glass, therefore, the lasing wavelength becomes very sensitive to the diameter of the constituent spheres and follows the resonances of the system. Figure 6b shows how the modes sustained by the spheres affect the laser output. In this figure one can observe a controlled overall shift of the lasing wavelength of about 35nm between different photonic glasses composed with spheres with diameters d = 0.9 μm (yellow line) and d = 1 μm (orange line). Lasing modes from both systems are shifted with respect to the gain maximum; this can be explained in terms of Mie modes. Figure 6b compares the lasing wavelength dependence with the sample total transmission. For these two photonic glasses, the Mie resonances are pronounced, with maxima and minima shifted, even if the difference in the diameter is only 0.1 μm. A minimum in transmission corresponds with a maximum in the scattering strength of the system. Light with this wavelength populates a Mie mode in the structure and dwells longer in the spheres, enhancing the light/dye interaction. Thus, the system tends to lase where the scattering strength is maximum, even far from the gain maximum. The limited gain puts a limit on the wavelength shift induced by the scattering resonance [Patent: Method for the spectral control of the emission of a random laser. WO2009150276-A1; ES2330714-A1; ES2330714-B1].

Finally, during my research at the Niels Bohr Institute, we explored Anderson localization in disordered photonic-crystal waveguides where the residual fabrication imperfection is sufficient to obtain very efficient and broadband tunable random lasing with remarkable output stability and very small mode volumes [Nature Nanotechnology, 9, 285 (2014)], (see Fig. 1c-f). We explored the properties of random lasing in photonic-crystal waveguides by increasing the optical gain material in the nanostructure in the form of embedded InP quantum wells. The unavoidable imperfections just due to the fabrication process are sufficient to create disorder-induced optical cavities which provide the necessary optical feedback for lasing by increasing the excitation power. Very efficient and broadband tunable random lasing with remarkable output stability and very small mode volumes was observed in these nanostructures Embedding light emitters in Anderson localized random media provides a promising new route to an enhanced light–matter interaction relying on the natural occurrence of cavities in random media rather than nano-engineering. I am currently exploring this rich and intricate physics. The potential applications of low-threshold nanolasers and highly efficient single-photon sources are very attractive because the relevant figures of merit for these applications match engineered systems, with the added value that random structures could be much easier to fabricate. The fundamental limits of the disordered media are yet to be explored, but their performance is likely to be improved even further by deliberately mixing the amount of order and disorder in the structures.