Material science for photonics

During the initial stage of my research career, I focused on the materials-science foundations of photonics. I carried out my PhD at the Instituto de Ciencia de Materiales de Madrid (CSIC) under the supervision of Prof. Cefe López, where I studied the fabrication of three-dimensional self-assembled nanostructures and their interaction with light.

From ordered photonic crystals to completely disordered structures known as photonic glasses (Fig. 1b–c), the central goal of my PhD was to exploit the interplay between order and disorder to control light transport.

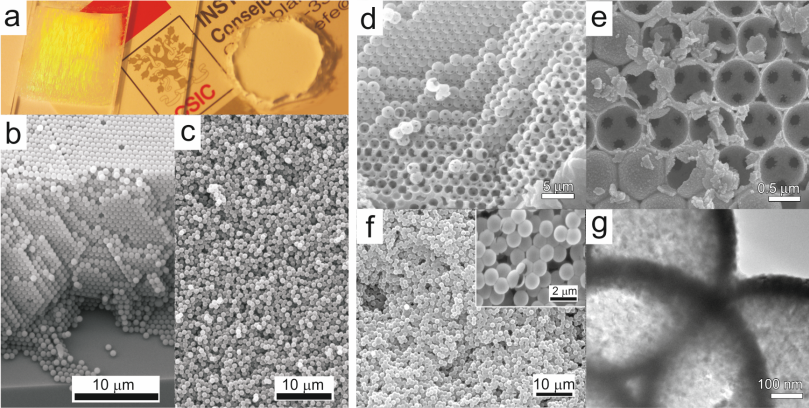

Fig. 1. Self-assembled photonic structures

(a) Self-assembled photonic crystal (left) showing visible iridescence due to Bragg reflection, and photonic glass (right).

(b–c) SEM images of these two structures.

(d–e, g) ZnO photonic crystals fabricated by chemical vapor deposition using self-assembled opals as templates.

(f) ZnO photonic glass obtained using the same technique.

Artificial opals: from order to photonic crystals

From the Sanskrit upala (gemstone), an opal is a self-assembled face-centered cubic (fcc) lattice of monodisperse dielectric microspheres. Natural opals, composed of SiO₂ spheres, display vivid iridescence due to Bragg diffraction from crystallographic planes (Fig. 1a). Because the sphere diameter is comparable to the wavelength of visible light, these structures act as three-dimensional photonic crystals.

By mimicking nature, artificial opals can be fabricated using polymer microspheres (polystyrene or PMMA). These are the only scalable three-dimensional photonic crystals with strong optical properties. I used these polymeric structures as templates to fabricate inorganic photonic crystals in ZnO using a controlled metal–organic chemical vapor deposition process, achieving large-area, high-quality structures with tunable filling fraction.

ZnO exhibits strong excitonic UV photoluminescence at room temperature, which can be further enhanced by nanostructuring. Using these ZnO photonic crystals, I demonstrated UV lasing driven by the interplay between periodic feedback and optical gain. The strong dispersion and reduced group velocity in the photonic band structure provide the feedback necessary for light amplification, leading to a clear lasing threshold.

Photonic glasses and resonant diffusion

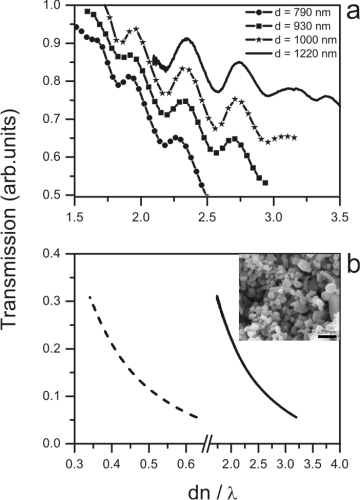

Fig. 2. Resonant diffusion through photonic glasses

Another central direction of my PhD was the study of photonic glasses (Fig. 1c): fully disordered self-assembled structures. Unlike ballistic transport in homogeneous media, light in photonic glasses undergoes multiple scattering and diffusive transport.

Remarkably, when the constituent spheres are monodisperse, individual Mie resonances occur at the same frequency in every scatterer. As a result, the diffusion of light becomes resonant, producing pronounced features in the transport mean free path, diffusion constant, and energy velocity (Fig. 2a), in contrast to conventional random media (Fig. 2b).

Using static and dynamic measurements, I demonstrated for the first time a diffusive resonant material, combining dispersion and diffusion within the same system (Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 233902 (2007)).

Controlled disorder: from crystals to glasses

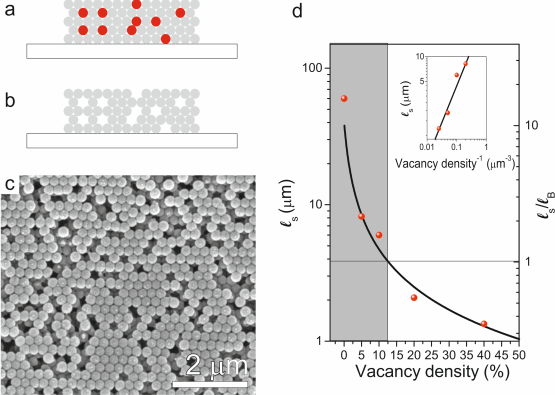

Fig. 3. Photonic crystals with controlled disorder

In the final stage of my PhD, I explored the intermediate regime between order and disorder. While photonic crystals are extremely sensitive to imperfections, this sensitivity also enables new physics.

We introduced disorder in a controlled and tunable way by creating vacancies in a three-dimensional colloidal crystal. Binary alloys of PMMA and polystyrene spheres were grown into fcc crystals. By selectively etching one component, we created a lattice with a controlled vacancy density (Fig. 3a–c).

This approach allowed us to tune the scattering mean free path without altering the underlying crystal lattice. As the vacancy density increased, the system crossed over from Bragg-dominated transport (ls ≫ lB) to diffusion-dominated transport (ls < lB), as shown in Fig. 3d.

At high vacancy concentrations (≈40%), the structures exhibited the same resonant optical behavior as fully disordered photonic glasses. This enabled us to observe a continuous transition from Bloch lasing in ordered structures to random lasing in disordered ones, demonstrating a direct link between structural disorder and lasing physics.

These results established a unified framework connecting order, disorder, diffusion, and lasing in three-dimensional nanophotonic materials, laying the conceptual foundation for much of my later work.