Random lasing

Nanoscale photonic devices require light sources with ultra-small mode volumes and extremely low thresholds. However, reducing the size of a laser cavity introduces two fundamental challenges: (i) the design of an efficient optical feedback mechanism at the nanoscale, and (ii) sufficient light–matter interaction to reach the lasing threshold with a very limited amount of gain material.

Nanostructuring the gain medium can address both challenges simultaneously. Interference within the nanostructure provides optical feedback, while field confinement enhances the light–matter interaction and reduces the lasing threshold. Conventional approaches rely on precisely engineered nanocavities, but unavoidable fabrication imperfections often limit device performance.

An alternative strategy is to exploit multiple scattering of light as the feedback mechanism. Multiple scattering increases the optical dwell time within the gain region compared to a bulk, unstructured medium, eventually leading to lasing when gain overcomes leakage. This phenomenon is known as random lasing.

Fig. 1. Random lasing in disordered nanostructures

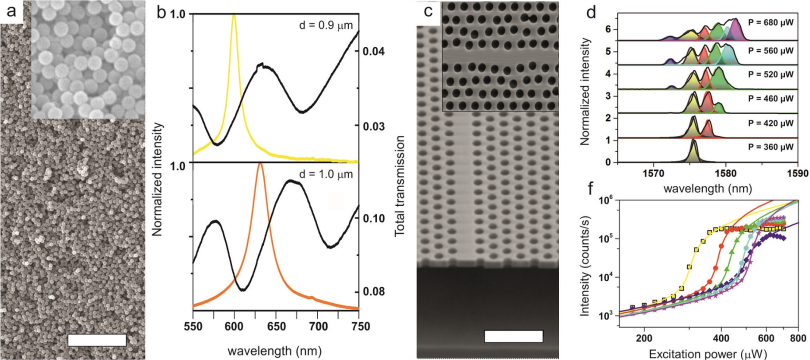

(a) Scanning electron micrograph of a photonic glass made of polystyrene microspheres (scale bar: 20 µm).

(b) The sphere diameter determines the random-lasing emission wavelength in dye-doped photonic glasses.

(c) Scanning electron micrograph of a photonic-crystal waveguide (scale bar: 1 µm).

Anderson-localized modes in this structure provide the necessary feedback for random lasing when quantum wells are embedded.

(d–f) Multimode lasing with remarkably stable output emission.

Figures adapted from Nature Photonics 2, 429 (2008) and Nature Nanotechnology 9, 285 (2014).

Early random lasers typically operated in the weak multiple-scattering regime, leading to multidirectional emission, poor mode confinement, strong mode competition, and chaotic dynamics. Moreover, the emission wavelength in these systems is usually dictated solely by the gain spectrum, offering little spectral control.

During my PhD, I demonstrated that photonic glasses — disordered assemblies of monodisperse spheres — can introduce spectral control through resonant multiple scattering. In these structures, the equal size of the spheres leads to Mie resonances that act as dispersive scattering channels. When optical gain is embedded (e.g., organic dyes), the lasing wavelength is no longer fixed by the gain maximum but instead follows the resonances of the scattering network.

By changing the sphere diameter from 0.9 µm to 1 µm, we achieved a controlled shift of the lasing wavelength of approximately 35 nm, even though the gain spectrum remained unchanged. This behavior arises because light at resonance wavelengths dwells longer inside the spheres, enhancing light–matter interaction. As a result, lasing occurs preferentially at wavelengths where the scattering strength is maximal, even far from the gain peak.

This concept led to the patent: Method for the spectral control of the emission of a random laser (WO2009150276-A1; ES2330714-A1; ES2330714-B1).

Later, at the Niels Bohr Institute, I explored random lasing based on Anderson localization in disordered photonic-crystal waveguides. In these systems, residual fabrication imperfections are sufficient to create disorder-induced optical cavities with extremely small mode volumes.

By embedding InP quantum wells in the waveguides and increasing the excitation power, we observed efficient, broadband, and tunable random lasing with remarkable output stability. The natural formation of Anderson-localized cavities provides the necessary optical feedback without any additional nanofabrication complexity.

Embedding light emitters in Anderson-localized random media therefore offers a powerful route to enhanced light–matter interaction, relying on the natural emergence of cavities in disordered systems rather than on deterministic nano-engineering. The potential applications of low-threshold nanolasers and highly efficient single-photon sources are particularly attractive, as random structures can be significantly easier to fabricate than conventional nanocavities.

The fundamental limits of disordered media are still largely unexplored. Their performance may be further improved by deliberately combining order and disorder, opening a rich design space for future nanophotonic light sources.